Energy accounting – not just for autism

Energy accounting transformed the way we supported Lily’s recovery. For Lily, it was a great tool to help her to understand how to continue her recovery and stay well School staff used it to manage her time table and I was able to work out what changes were needed to keep up on track. Lily was repeating Year 9 and in mainstream high school at this point. She had been desperately shut down and unwell for many months the previous year, and largely out of lessons, or out of school completely, for the previous 2 years.

What is energy accounting?

Lily’s psychiatrist advised we look at energy accounting in the earlier stages of recovering from quite this quite severe burnout, and for us, it was a game changer.

I had heard of theories that looked at careful spending of fixed levels of energy before, such as spoon theory, but a system to consider more of a balance – energy in and energy out, this was new and interesting.

Energy accounting (described here) was developed by Maja Toudal and is typically used to prevent, or support recovery from, autistic burnout. Lily isn’t autistic; however, a combination of trauma and masking ADHD had led to a severe and long term deterioration to her mental health.

I investigated it a little, thought about the best ways of approaching this with Lily and waited for a good time to talk to her about it. She needed to be in a good place, when thinking about a new concept wouldn’t burn her out for the rest of the day.

Talking to Lily about energy accounting

A typical approach used for energy accounting (taken from here) would look like this.

A typical approach used for energy accounting (taken from here) would look like this.

I didn’t think this would appeal to Lily and the scale (0-100) felt too big. Too much choice could overwhelm her, and she would have disengaged from the activity.

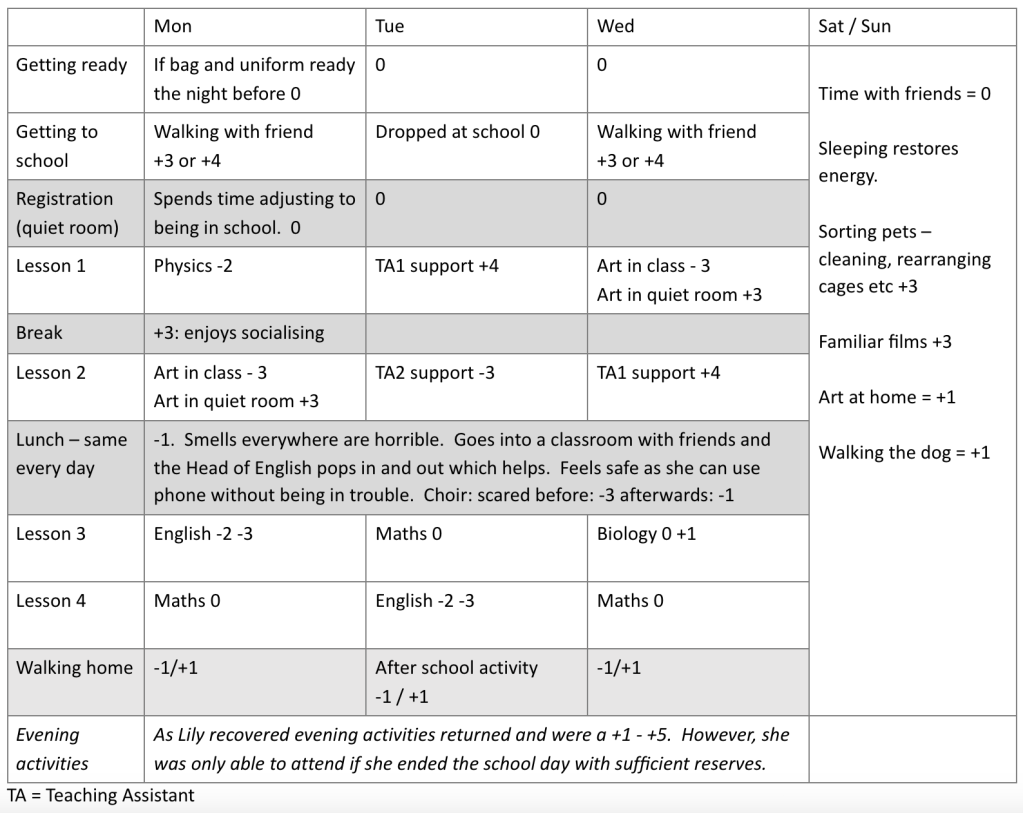

I decided to use a personalised timetable, based on Lily’s week, and explained that each activity can be energy draining or energy giving. We agreed a scale of -5 to +5.

We allowed plenty of time for Lily to think about the activities. She allocated the scores, but then she talked about how she felt in detail in some parts of the day. Below is a snapshot of part of that timetable. It is important to note that Lily enjoyed all these subjects – this isn’t about her ‘liking’ things – it is the impact of the activity on her. For example, choir she loves – but would need to ‘budget’ the energy to take part.

There were several unexpected benefits. For example, it clearly was not in Lily’s best interests for me to offer her a lift to school! Others are below:

- It was extremely helpful as a tool for Lily to explain what life was like for her hour to hour. I felt as though I understood what was going on for her much more accurately. Lots of useful conversation came as part of the activity.

- Tailoring the school support: within hours of the school’s special needs lead (SENCo) receiving the energy accounting, TA2 was swapped and new strategies for English lessons were explored and implemented.

- It was a great way to explain to people why, for example, when Lily couldn’t manage the English lesson, she could manage her after school activity.

We went on to revisit the idea of energy accounting when Lily looked like she was struggling again, to think how we needed to adjust her week so she could continue to recover and make progress. 2 years later, doing this is an automatic process for her. She notices when she is getting exhausted and changes her plans before she takes a backward step. Practicing energy accounting has given her new skills that are automatically incorporated into every day life.

Lily has made unimaginable progress over the last 2 years in her ability to live a full life. She still needs to prioritise rest, and to balance her activities so that she doesn’t overstretch herself and ends each day in a positive balance. I’m not sure Lily would have made such significant progress without:

- Lily developing a good understanding of how to balance and grow her energy reserves independently, and,

- all of us understanding the critical nature of extracurricular activities and their role in adding to energy reserves and growing resilience.

At her lowest, Lily was probably starting the day at less than 2% of battery power. By the time we looked at energy accounting she would perhaps at about 15%. Dr Alice Nicholls describes burnout as an energy debt, and the importance of finishing each day with a positive energy balance – to get out of the debt.

Thinking about this some more, and with the support of the SENCo and CAMHS, we continued to ensure that Lily’s school day allowed good many extra concentration breaks, a limited timetable and flexible finishing times – led by Lily. She built up her evening activities (these restore energy) as her reserves grew. We did this in preference to taking on more academic work or school hours. These boosted her energy and had added benefits such as increasing her skills, number of friends and her confidence. In turn her ability to cope with challenges at school increased, alongside her ability to contribute to the school community, and produce work that properly reflected her academic level.

We have learned:

- the importance of balancing energy sapping activities with emerging giving ones, planning ahead and prioritising rest and sleep daily,

- not to add to the academic timetable as Lily recovered. This way she could continue to end the day with a more positive balance, and to grow her extra-curricular ‘life’,

- prioritising extra-curricular activities was essential to aid recovery and resilience, minimise backwards steps and add to the degree of progress made,

- to revisit the energy accounting when Lily was struggling (progress is never linear).